Over two-hundred firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians died in the line of duty in 2014. Emergency response is a dangerous line of work that requires efficient coordination between the individuals and teams involved. Team Dado collaborated with Draper Laboratory to reduce this human cost by enhancing situational awareness for first responders.

TeamSense delivers location information to on-scene first responders. Team location is a critical piece of information for responders, enabling them to coordinate their actions, ensure the safety of themselves and one another, and speed rescue efforts. Location information is difficult to communicate over the radio; TeamSense gives responders a clear picture of where their teammates are by layering sound and visuals over the responder’s perception.

Dado researched emergency response in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Through a combination of structured interviews, directed storytelling, contextual inquiry, and guerrilla research we immersed ourselves as deeply as possible in emergency response without actually setting foot in a burning building. After gathering data, we synthesized our findings and modeled how information flows through a scene to identified two primary problems that we wanted to address with our prototype.

First responders communicate primarily through radio. The radio is great at broadcasting information to a large group of people, but only allows one person to communicate at a time.

As scenes become increasingly complex, responders are forced to restrict their communication to conserve radio bandwidth. During these bandwidth crunch times, responders must make guesses about what others need to know and weigh the value of each piece of information before deciding whether or not to broadcast it. Additionally, radio channels become saturated as scenes expand, delivering a constant stream of information. Responders must begin to sift through the information they receive to determine whether it’s relevant to them. The scaling limit of radio channels adds a layer of mental strain to already stressful large-scale emergencies.

Since information is not automatically prioritized and responders are left to make prioritization decisions on their own, each responders’ idea of what is important may slowly cease to match. Emergency responses are collaborative efforts, and the actions that each responder takes depend heavily on a shared understanding of the scene. When responders are unable to communicate their understanding with the rest of the team, collaboration starts to break down. This is especially problematic in large-scale scenes, where scene chaos can quickly overtake the ability to communicate. Due to the nature of emergency response, these communication breakdowns can have deadly results.

In order to understand first responders, Dado used human-centered research methods. These methods are structured to capture and synthesize the experiences, expertise, and wisdom of our target population and foster rich insights.

Expert interviews provide foundational, “onboarding” knowledge of a domain. Taking on a “master - apprentice” dynamic allows experts to share and describe their experiences in a manner that supports researcher learning and understanding. We interviewed emergency responders and individuals from analogous domains to understand their experiences. Planning for both structured and unstructured parts of interviews allows researchers to direct the conversation to relevant details while allowing conversation to flow organically at times to hear candid stories and experiences from experts.

In our initial interviews, we realized that responders had a tendency to tell us how things should work and not how things do work. A directed storytelling exercise allows researchers to keep an interviewee focused on their most recent relevant experience, sticking to the facts and revealing both the breakdowns that occurred and the causes of those breakdowns. Capturing this information in the interview allowed us to clarify any unknowns in the moment, ensuring we made the most of our time in the interview. We captured this information using a custom-designed field guide.

Reviewing academic and secular publishings allowed us to obtain a foundational knowledge of the emergency response domain, focusing on signal salience in high-stakes and uncertain situation, and decision-making. Beginning with the literature review ensures our team knows what’s been discovered about the landscape we’re working in. It allows us to sketch out current knowledge about the domain and select the “uncharted territories” we’d like to explore.

Immersion and empathy training allow researchers to walk a mile in their user’s shoes, revealing nuances and expert blindnesses that may be missed in interviews and directed storytelling. We invited a firefighter we had previously interviewed to come train us on what a fire response experience is like. He instructed us on ways to simulate the factors in a fire search and rescue mission without actually putting ourselves in danger.

First responders face situations that are almost entirely unparallelled in our day-to-day experience. We wanted to get in first responders’ shoes by experiencing as close as possible their jobs. We heard of a fire that was taking place in a neighborhood in Pittsburgh called Bloomfield. We went to the scene and were able to observe and map how responders interact with each other and how they coordinate.

A ride-along allows researchers to spend an entire shift with their user and understand all aspects of their workflow. Team members spent 51 hours on 6 ride-alongs with firefighters, EMTs, and police. This research activity allowed us to get as close as possible to the actual experience of being first responders. We were able to see first hand how firefighters, EMS and police operate on a daily basis and the experience that they have on the job.

Journeymaps visually display the workflow of a user. This tool is often used to identify breakdowns in the workflow, however, we used it as a way to check our understanding of the emergency response environment. We created a skeleton of a journeymap and then brought it to interviews with emergency responders. Working with them, we re-created the moment to moment breakdown of a scene, helping us better understand each component. Co-creation allowed us to check the accuracy of our assumptions in the moment and encouraged those we interviewed to discuss the reasoning (and history) behind protocol.

Affinity mapping is a process where knowledge gathered in the research phase is broken down into single bits and then put back together based on related concepts. This process facilitates insight generation as it integrates seemingly disparate information into the underlying patterns and trends. We used affinity mapping to process all of our field research and literature review.

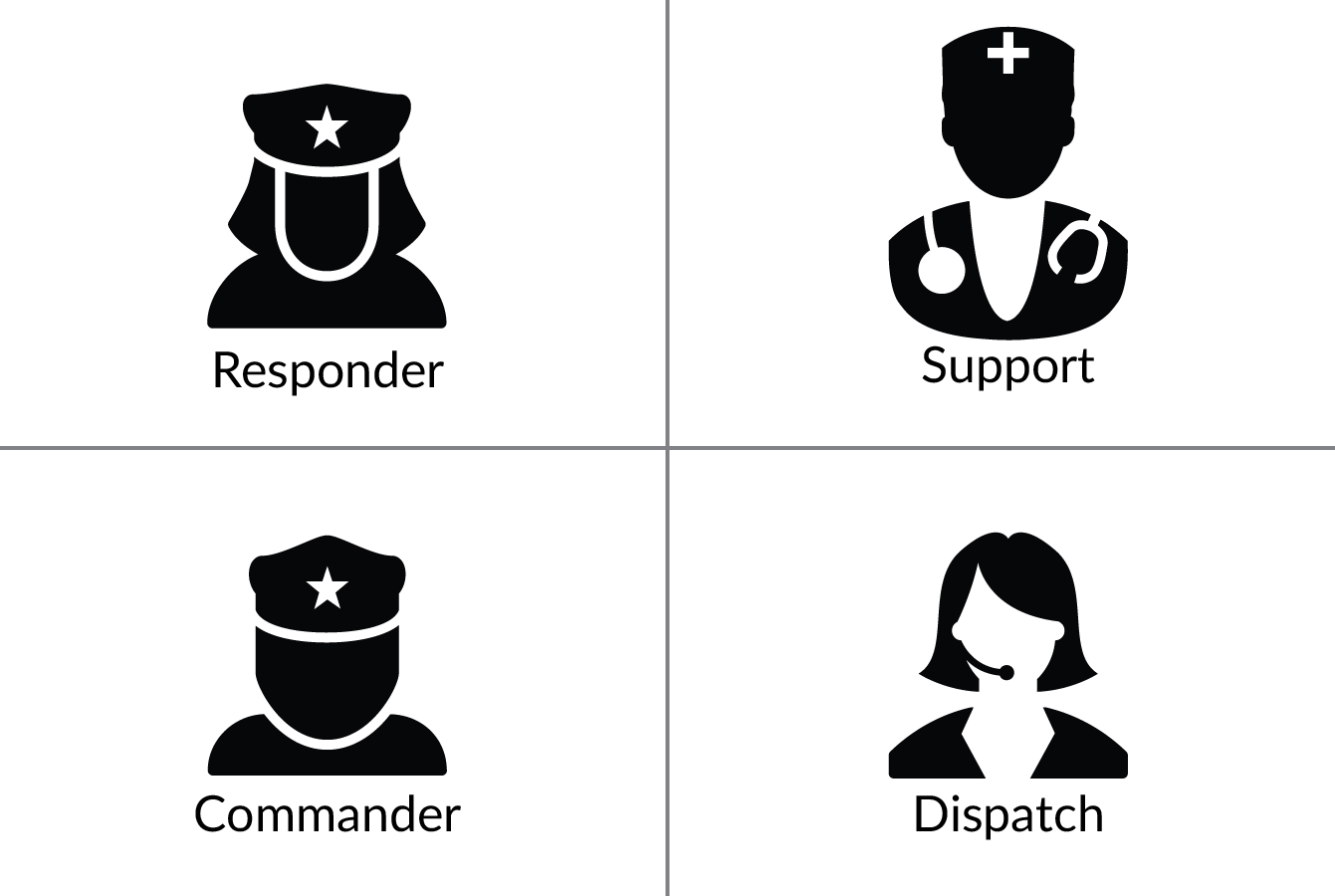

We modeled each role involved in emergency response along 2 axes: proximity to the scene and amount of resources managed. Through visualizing the roles in this manner, we made an informed decision to design for those involved in low resource management with direct proximity to the scene.

After determining what information is most important to first responders, we designed ways to deliver that information. We explored visual, audio, and haptic presentation modalities, focusing on signal clarity and intuitive understanding. By focusing on intuitive understanding, we can provide responders with the information they need without distracting them from the emergency scene and without the need for prior learning.

We bodystormed our concepts to quickly weed out weak presentation methods and determine which ones to develop further. Using rapid prototyping, we could cheaply test new ideas as they came. We tested many kinds of presentation modalities and were able to narrow our scope to the ones that proved promising. For example, we found users could not easily decide how to act when told that a room was partially searched.

Intuitive modalities allow for the simultaneous conveyance of multiple pieces of information. Other modalities are less intuitive and work better conveying single pieces of information. Some information is intuitively understood on one modality but not on others. Our low-fidelity prototypes and mockups allowed exploration of each modality’s strengths and weaknesses. In this case, we successfully conveyed that an objective was a floor below the user by showing them photos paired with different head-up displays.

We tested multimodal combinations of presentation methods against each other to determine the best combinations. Some presentation methods intuitively paired with the data they displayed, minimizing cognitive overload. We found that participants had difficulty integrating information from different modalities, such as distance through haptics and direction through audio. However, users could process information on different modalities if the information is already combined in a way that makes it actionable.

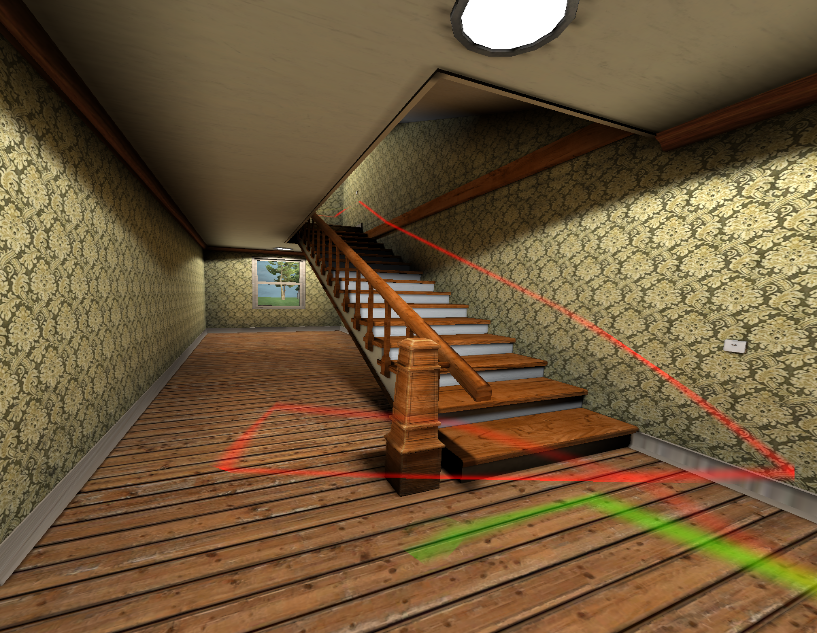

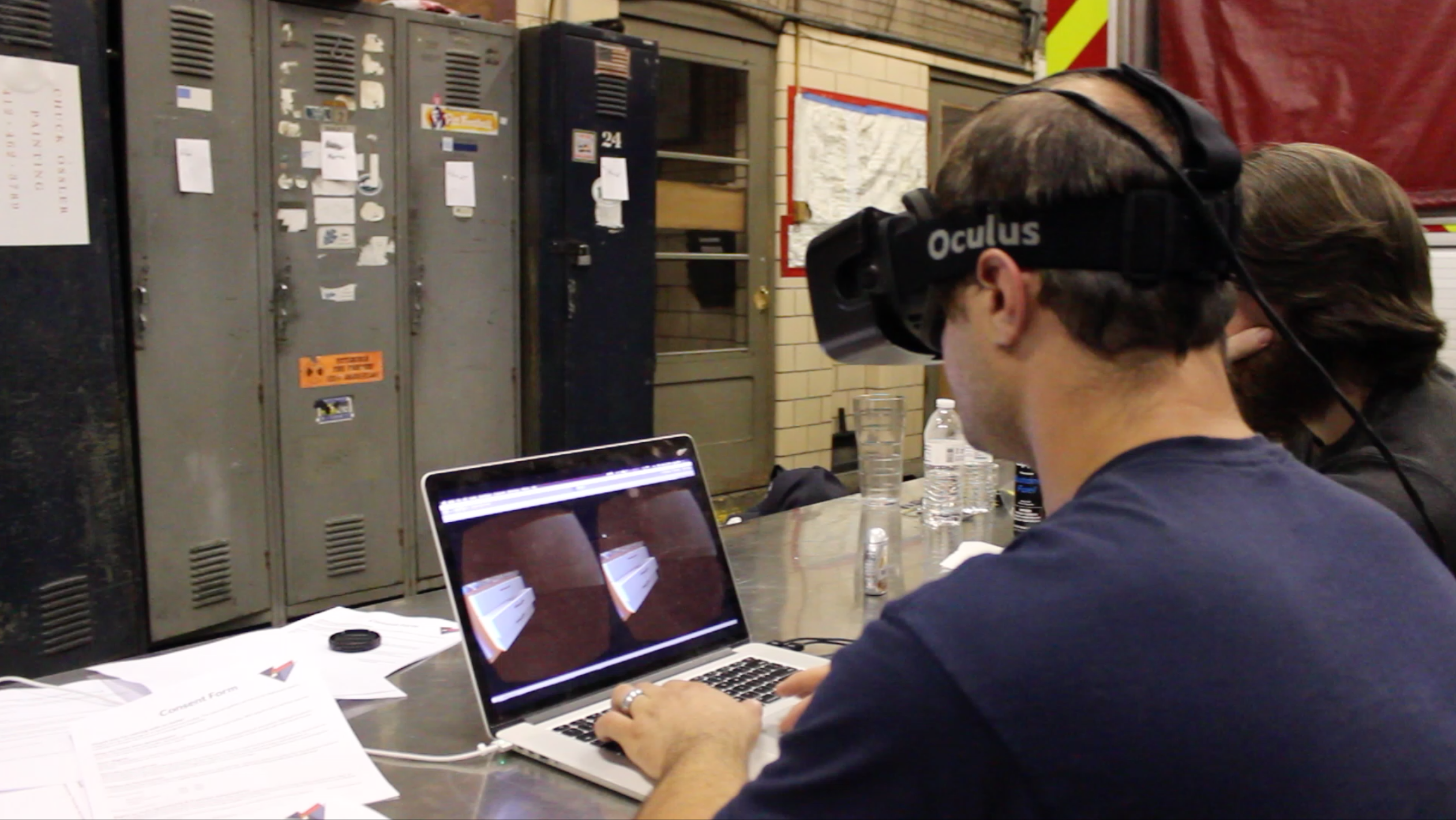

Our prototype needs to display information despite the stress and distractions of real emergencies. We built a virtual environment that simulates the danger, uncertainty, and time pressure of fire response, deliberately placing users under a high-cognitive load. We designed our testing environment and prototype with these pressures in mind, giving users the information they need to search the building without distracting them from environmental cues.

We stress tested the prototype by placing users in a virtual high-rise building fire. The scenario progresses through three use cases: clearing a floor as a team, receiving a critical alert about the safety of the a teammate, and targeted rescue and extraction. The scenario includes air management, impaired vision from smoke, and radio distractions. We designed a testing protocol to measure the attention balance between prototype display and environmental infoamtion in the scenario. Testing with this scenario allows us to validate that our prototype reduces cognitive load in different contexts.

Responders are placed into extreme situations that hinder their ability to perceive information. The audio channel is overloaded with radio chatter, and vision is impaired by smoke. Our prototype needs to work with existing input without creating additional overload.

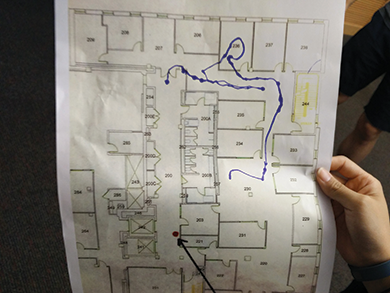

Responders rarely have a full picture of what is happening and need to be comfortable dealing with uncertainty. We built out a complex floorplan designed to disorient participants and tested their ability to formulate plans from limited information.

Effective coordination becomes increasingly difficult as more responders are called in to the scene, as team communication is in a constant race with evolving hazards. We required participants to respond to recorded radio chatter to ensure we don’t distract them from what others are doing.

We are a group of interdisciplinary students in the Masters of Human-Computer Interaction program at Carnegie Mellon University. More than a team, we are a family that has learned to rely on each other and grow from each others’ mentorship. Beyond our research work, we feed our philosophical bent by engaging with the perennial question, “But is it BBQ?”

Tess comes from a behavioral economics research background, with experience in management and a passion for startup companies. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the University of Pittsburgh.

www.tessbailie.com

Ryan comes from a user research background, with experience in ethnographic research and startup management. He is interested in the ways technology can affect behavior and facilitate new forms of interpersonal interaction. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Sociology from Wesleyan University.

www.ryan-brill.com

Alan is passionate about creating technology that is transformative like the app that wrote this bio in the third person for him. He completed his undergraduate degree in 2014 at Carnegie Mellon where he studied Human Systems and Human-Computer Interaction.

www.alanherman.net

Jim has a background in Generative Art and Design with a degree from NC State university. He’s broadly interested in interaction design, data visualization, and how HCI can push those disciplines forward.

www.jimmartininteractive.com

Zack comes from a development background, and is primarily interested in information architecture, interaction design, and educational technology. He graduated from the University of Virginia with degrees in Computer Science and Religious Studies.

www.zacharyaman.com