Mission Statement

To design a smart home system in which users can manage smart devices for their routines and have easier control of their personal data.

Devising a smart home system that mediates personal data privacy

Bosch is an engineering and electronics company founded in Stuttgart, Germany in 1886. They specialize in consumer appliances, mobility technologies, and building infrastructures. The rise of sensor- based technology and the Internet of Things (IoT) has raised public concern regarding end user security and privacy. People do not fully comprehend the implications of using these systems, and feel betrayed when they perceive that their data has been misused.

Users lack adequate resources to make informed decisions about their individual privacy. This discrepancy is adverse to the relationship between sensor technology manufacturers and consumers. While it is expected that users have personal interest in their own privacy, it is the responsibility of the manufacturers to communicate their policies in a transparent, straightforward manner. Bosch and Haven are working together to devise an intuitive smart home system that improves users’ overall quality of life, while respecting their personal privacy.

We recruited a wide range of participants and altered our methodology based on the particular demographic we decided to cater to for each cardigami trial. Our first participant pool consisted of working professionals, and then expanded to include students, families, elderly and new moms.

To design a smart home system in which users can manage smart devices for their routines and have easier control of their personal data.

Creating an integrated smart home experience while respecting personal privacy

The rise of sensor- based technology and the Internet of Things (IoT) has raised public concern regarding end user security and privacy. Users lack adequate resources to make informed decisions about their individual privacy. This discrepancy is adverse to the relationship between smart device companies and consumers. While it is expected that users have personal interest in their own privacy, it is the responsibility of the manufacturers to communicate their policies in a transparent, straightforward manner.

Moreover, the Internet of Things market is relatively new and only a limited selection of products are available; none of which allow users to easily connect and control smart devices. The market’s current offerings are fragmented, made by different manufacturers whose business interests do not align with Bosch’s vision of creating an integrated smart home experience.

Bosch and Haven are working together to devise an intuitive smart home system that improves users’ overall quality of life, while respecting their personal privacy.

Research Goals

Evaluating users’ interests regarding home security and privacy.

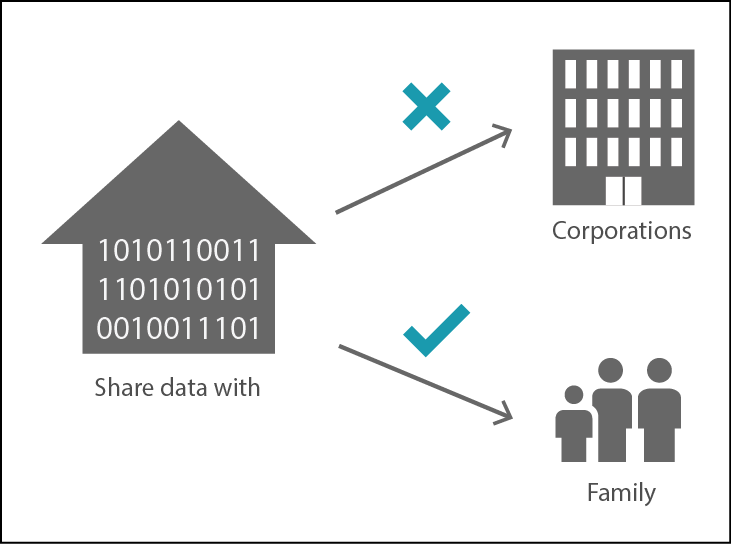

Coming into this project, our first goal was to understand users’ mental models regarding data and privacy at homes. In the generative phase of our research, we intended to investigate how much users care about the privacy of their data, why they care, and where the boundaries are. Through surveys, interviews, and hands-on exercises, we examined users’ levels of comfort sharing various types of data with different actors. This will help us identify problem areas where the Bosch model can come in to resolve their privacy concerns.

Our second goal was to test users’ understanding of the Bosch model and the benefits it provides in protecting their privacy. We also wanted to investigate users’ mental models of the current data flow to examine whether they are aware of the privacy risks it presents. Once we understand users’ mental models, our mission was to inform users about the problems of the current data system and provide Bosch’s solution.

Our third goal was to make sure the UI of the system is simple and intuitive for users. In the evaluative phase of our research, we focused on how we can seamlessly integrate Bosch’s system into people’s lives.

Research Methods

Interviews

Surveys

Cardigami

Speed Dating

To understand people's mental model of privacy

We interviewed seven participants to get a better understanding of a person’s mental model of privacy around smart devices and how data is stored. We asked them about their experiences with smart devices such as smart watches, fitness trackers, smartphones etc., and then made them think about how their data is used. After priming users in this domain, we then subtly introduced aspects of Bosch’s conceptual model of smart homes, UPA Platform, to gauge their reactions. Through a daily reconstruction activity, participants recalled events that happened in the past day to come up with examples of how this model could make their lives easier. We also asked them to consider whether or not they would use such a system.

To assess people's willingness to shared data

We wanted to gain insights about perceived utility and users’ willingness to share certain types of data across a spectrum of actors. We distributed two rounds of surveys on Mechanical Turk and both of which received 80 responses each for a total of 160. The first round of surveys focused on personal health monitoring and home energy usage monitoring. We asked users how comfortable they felt sharing data with different types of actors: family, friends, neighbors, doctors, corporations, and the government. For the second round, we wanted to investigate boundaries and use cases in which they were not comfortable sharing health monitoring and smart meter data. This time, we kept the actors constant, but tested the user’s willingness to share based on different applications of their personal data.

To explore potential use cases of the conceptual model

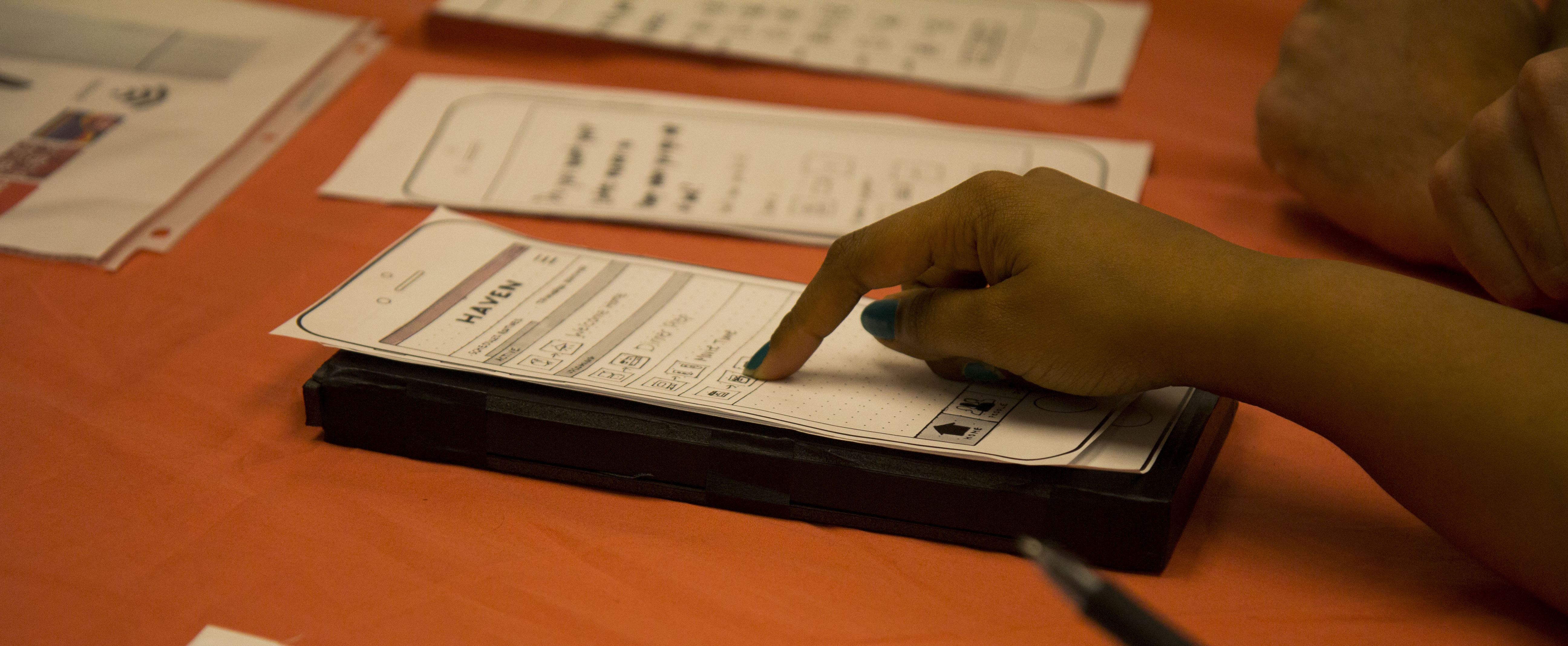

Cardigami is a mix of two design research methods: card sorting and business origami. Card sorting is a method that requires participants to organize cards into categories that make sense to them. Whereas business origami is a method that uses paper cut-outs of people, buildings, etc. that represent various stakeholders within a system to prototype interactions. We view it as part exploratory and part generative method.

We presented the participants with a deck of cards with pictures of smart home objects on them. They were then asked to sort the cards into groups that made sense to them. We then introduced participants to paper cutouts representing various parties who could have access to their personal data (e.g. people, corporations, and the government) to generate a miniature model of a system. Our main objective was to investigate participants’ security and privacy concerns in relation to these smart home objects. The participants arranged the paper cutouts in appropriate groups based on who they wanted to permit and disallow data access.

We recruited a wide range of participants and altered our methodology based on the particular demographic we decided to cater to for each cardigami trial. Our first participant pool consisted of working professionals, and then expanded to include students, families, elderly and new moms.

Investigating boundaries around data sharing and privacy

Speed dating is a design method for rapidly exploring application concepts and their associated interactions. It is a low-fidelity technique that combines aspects of sketching and prototyping; it is used to test and evaluate the validity of new ideas. Speed dating facilitates the comparison of various relatable concepts, and helps researchers identify contextual risk factors to develop meaningful solutions.

We conducted speed dating sessions with new families and parents to test social boundaries of security, privacy and monitoring within the home. The scenarios were intentionally designed to provoke users to think about how these scenarios might apply to them.

From our cardigami sessions, we explored four different demographics: working professionals, students, elderly, and moms. As we analyzed the insights along with the use cases the participants generated, we concluded that new parents would be Bosch’s ideal target audience.

Research Insights

Introducing KIN

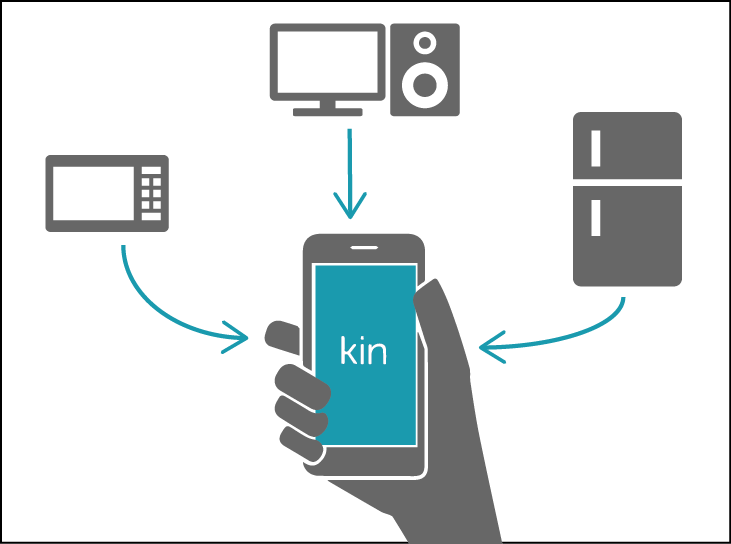

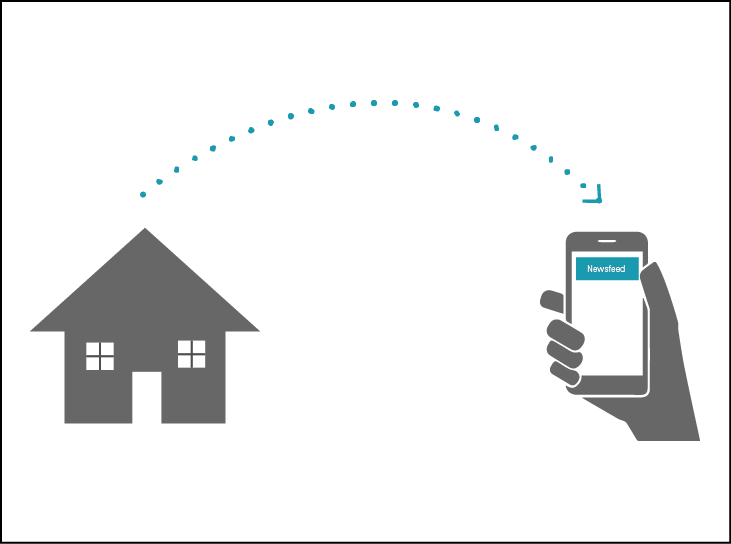

Kin is a proposed family-aware mobile system to integrate Bosch into smart homes. With Kin, users can create routines around smart devices, manage data, and share access with others, all while safeguarding users’ privacy.

Sam decides to turn his home into a smart home. As he buys more and more smart devices, he adds them to Kin to control and manage them with ease.

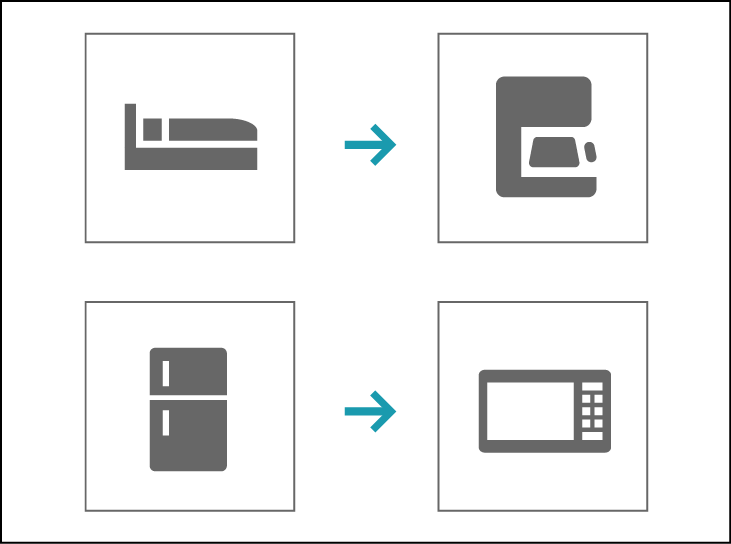

With the help of Kin, Sam creates connections between his devices that can help him easily do his everyday routines. For instance, his coffee maker will now brew coffee whenever he gets up.

When Sam has visitors over, he can effortlessly share access to his devices with them through Kin’s intuitive interface.

Sam cares a lot about his privacy and security. Kin allows him to conveniently control data that flows in and out of his smart devices.

Sam enjoys his new smart home experience. Even with so many tasks happening in the background, he is not overwhelmed, because Kin shows everything he needs to know about his smart home, providing timely updates to him.

User Enactment

Setting the scene for Usability Testing

Smart home technologies have only recently entered the market and most people have yet to adopt them. User enactment is a method specifically used to explore new design spaces and test futuristic concepts. The goal was to provide our participants with an appropriate context that would encourage them to think freely about a futuristic smart home system.

We transformed an ordinary classroom into a smart home setting complete with appliances and props crafted from foam core. The room consisted of five distinct areas that represented various spaces inside and outside of the home: front porch, living room, kitchen, dining room, and office. We wanted to simulate the behavior of an actual smart home through tangible interactions with our constructed models. Furthermore, we incorporated scenic elements to our setup such as cobblestones, pantry, and house siding to make it feel realistic. Our simulation successfully primed users to think about future home technologies, which spurred the co-creation of original design ideas.

We devised four scenarios intended to test key aspects of our mobile application prototype: • Adding a new appliance to the smart home • Creating a new routine • Remote monitoring and event escalation • Creating a sphere and granting data access Participants were instructed to enact each scenario with the help of a narrator, and for our low-fidelity testing sessions, supplementary actors played by our three of our team members. The three actors: “App,” “House,” and “Data,” were personifications of abstract qualities that normally would not be made explicit in real life.

Lo-Fi Prototyping

From our low-fi prototyping we gained insights to improve the UI and identify more effective value propositions. With our 17 participants we learned how to strengthen the mental model of routine generation, sharing access, and data management. Through reactions to our user enactment scenario and follow-up questions we were able to probe participants on where the greatest value would be for them with a system like Haven.

Mid-Fi Prototyping

We conducted 9 usability testing sessions. We expanded our testing demographics to further different geographical area for more diversity. In this version of prototype, we moved from paper prototypes to InVision. We shifted our testing strategy to include less concept validation, but more task completion testing.

In the current version of Kin, users can add time and event-based Triggers to their Routines. Two types of triggers that we would like to be included in future versions of the application are: People and Environment Triggers. People Triggers are instances where a routine will only be executed if specific people are involved. Environment Triggers refers to environmental factors like weather conditions and air quality.

Throughout our research, our participants frequently expressed that they would like it if the smart home system could support natural language input. Some additional input methods we believe could increase usability include manual gestures and body movements, such as waving one’s hands in front of lights to turn them on or off. We believe that multimodal user interfaces will become a key feature as smart home technologies advance and become more sophisticated.

The abundance of connected devices within smart homes provides opportunities for ambient displays. It is a new way of displaying information at a glance, without increasing cognitive load. For example, the daily weather forecast could be projected onto the surface of a bathroom mirror. Ambient displays will extend Kin’s user interface beyond mobile devices to physical smart home environments.

Eric Yi grew up in Taiwan and graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a B.S. in Business Administration. He is passionate about combining his business and design skills to solve problems. Eric also enjoys playing tennis and is currently learning guitar.

Jess hails from New York and fell in love with design in Pittsburgh during her sophomore year at Carnegie Mellon. Although she is a history major by trade, she has previously worked in both technology and advertising. Outside of her studies, Jess loves to ride her bike and play with her dog, Kaya.

Nirman studied architecture at UC Berkeley and has worked in communication management. During her last architecture studio at Berkeley, she explored how communication influences design. This inspired her to apply her form-based design training to communication management which allowed her to directly shape user experiences.

Lisa studied psychology and fine art at Carnegie Mellon. During her undergraduate years, she worked as a research assistant and spent a summer as a UX Intern at Bentley Systems in Philadelphia, PA. She especially likes to apply her research skills to create human-centered design. Lisa loves to spend her free time drawing.

Jeel is a designer-developer who found her passion in using technology to design for this user-driven world. Originally from Mumbai, she likes to indulge in casual photography and portrait sketching. Jeel is also a travel enthusiast as well as a foodie. Her philosophy is that human-centered design is critical towards the fruition of any idea.

Acknowledgments

Haven would like to thank the faculty and staff at Carnegie Mellon University’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute for giving all of us this unique opportunity. Many thanks to João Sousa and the rest of the folks at the Bosch Research Center. Thank you for believing in us. All of us want to especially thank our faculty mentors, Jason Hong and Skip Shelly. We would have never been able to get this far without your guidance and support.

Jason Hong is an Associate Professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute, part of the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University. His research focuses on ubiquitous computing and usable privacy and security.

Skip Shelly is the Director of Design Practice at Summa Technologies. He is a graduate from Carnegie Mellon University School of Design. He has previously worked at Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute.

The capstone project is a unique opportunity for masters students and the companies that sponsor them. Its is structured to cover the end-to-end process of a research and development product cycle, while working closely with an industry sponsor on improvements, modifications, or new applications to their existing human-to-machine technology.