Puerto Rico Case Study

We went to Puerto Rico to learn directly from Hurricane Maria survivors.

Overview

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated the island of Puerto Rico, taking over 4600 lives and

causing $85 billion in damage. We traveled to Puerto Rico in February 2018 to meet locals, first

responders, aid workers, and Eaton employees. We wanted to discover the real impact of a natural

disaster on a community. Even six months after the hurricane, 40% of the population was still

living without electricity.

We anticipated hearing stories about living without power. Instead, we heard stories of silence

- always wondering if friends and family were safe, and never knowing when help was coming. Our

original goal of reconnecting the lights became reconnecting people.

An Island in the Dark

Through secondary research, we sought to understand Puerto Rico at a broad level before we started travelled and started conducting interviews. We discovered that Puerto Rico has a myriad of factors that worsened the devastation caused by Maria. These factors affected both the immmediate aftermath and long term impact of the storm.

Aging Infrastructure

Before Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico had one of the oldest operating power systems in the United States, much hadn't been updated in 60 years. Power lines and substations were not well maintained, and thus were heavily damaged by flying debris and landslides.

Geography

Puerto Rico is an island in “Hurricane Alley,” a stretch of the Atlantic Ocean prone to tropical storms. Hurricane warnings are so frequent that they often go ignored. As an island, the only entry points for resources are the ports and airports. The center of Puerto Rico is mountainous and difficult to develop.

Centralized Power

Puerto Rico’s electricity is generated in only two locations on the island’s coast, in the direct path of any tropical storm. Hurricane Maria also destroyed many electrical substations, cutting off power for thousands of people on the grid. Electricity is generated by oil and natural gas, both of which have to be imported.

Political Landscape

All power on the island is supplied and maintained by the state-owned Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority. (PREPA) The agency was in significant debt before Hurricane Maria, and nearly 60% of its workforce retired within two years before the storm.

On the Ground

We chose to visit Puerto Rico to speak with hurricane survivors, and to visit the Eaton manufacturing plant that had withstood the hurricanes in September 2017. Prior to this, we conducted extensive secondary research, mainly through news articles and online interviews of government officials, relief agencies, and disaster management experts.

We reached out to people in our personal network, and recruited on LinkedIn and through disaster relief nonprofit websites to find interview participants. Our goals were driven by insights derived from secondary research and expert interviews, and were mainly regarding power management issues during disasters. We knew that multi-stakeholder collaboration is an issue in planning for disasters, but assumed that we would find that lack of power would have been everyone’s greatest obstacle.

Codesign Session and Collective Story Harvest

We got in touch with a local NGO, ACUDE, before we arrived in Puerto Rico, and met the director of the organization upon touching down on the island. Months after the hurricane, she still did not have power in her home or her office. She travelled to a nearby Starbucks for power and to find cell service. Despite working for a nonprofit working to teach survival skills to help people prepare for disaster, she conceded that the island was not prepared enough. After an insightful interview with ACUDE’s director, she got us in touch with her colleagues for a collective story harvest and participatory design session the next day.

We gathered six women and one young man during an afternoon to listen to their stories and understand their ideas for solutions. After splitting into two groups to listen to their stories of what happened before, during, and after Hurricane Maria, we all worked together to co-create an affinity diagram of the largest problem areas that come from a massive natural disaster. They told us their stories of sharing food with neighbors, logistical difficulties of waiting countless hours in line for gasoline, and the loss of family members due to stress and illness.

The mood in the room was hopeful, but also reflected a deep disillusionment with aid organizations, private corporations, and government who could not provide the relief that was promised.

After reflecting on the broad areas of opportunity to design better solutions, we again broke out into small groups to draw and discuss possible solutions to improve disaster relief and resilience in the future. Their designs involved increasing transparency in aid organization activities, as well as communication solutions to allow victims to reach family members more quickly.

Story Harvest Insights:

Health

One participant’s brother needs daily kidney dialysis, but did not always have access to the necessary power after the hurricane.

Transportation

The roads were covered in debris after the hurricane, and public utilities were slow to act. After several days or weeks neighbors banded together to clear the roads of trees and branches.

Food/Water

Everyone agreed that food donations from aid organizations were often unhealthy and provided an unbalanced diet. Some people stopped eating for days at a time for fear of not knowing when food would come again.

Money

ATMs and banking systems were down for weeks, so everyone had to pay for basic needs in cash — if you didn’t have change, sometimes an item would cost $20 when it should have been $1.

Communication

The first thing on anyone’s mind after the hurricane: “Is my family ok?” Dozens of local businesses closed, including big chain stores like Walgreens and Walmart, and employees did not know when they could go back to work and receive income.

Social Impact

Neighbors, friends, and family reluctantly fled from Puerto Rico, as utilities had been too slow to rebuild.

Interviews

We conducted interviews with various groups in Puerto Rico: locals, PREPA (the local energy utility company), business owners, and Eaton employees. These interviews gave us a more complete understanding of multi-stakeholder collaboration in disaster relief, as well as the day-to-day challenges for hurricane survivors.

Guerilla Research

The day we arrived in San Juan, we spoke with a couple from the south of the island, one a doctor and the other passionate animal rescue volunteer. They cited income inequality, systemic poverty, and an unhealthy population as vulnerabilities that were exacerbated by hurricane devastation. No one is prepared to spend months without power — especially those who live paycheck to paycheck. “Hurricane Maria has shown the world how poor Puerto Rico is,” they said. They are proud of their people, but recognize the deep inequalities that cause their neighbors to struggle even more the face of a catastrophic natural disaster. They are hopeful for the future, but remain skeptical of the current system in place to help people.

We spent an afternoon with a local of Canóvanas, about 18 miles from San Juan, that was still without power in February. She had to rely on her workplace for Internet, and FEMA for generator fuel and food at home.

Eaton Employee Interviews

Our client, Eaton, arranged for us to visit their manufacturing plant in Arecibo, about an hour west of the capital of San Juan. They scheduled for us to interview ten Eaton employees. They worked in a range of departments, but their stories aligned in one big way: Eaton provided immense support to employees after the hurricanes. We learned that the Eaton manufacturing plant was well-prepared, and got back up and running within two weeks — much sooner than other facilities. They were fortunate enough to work for a large company with the resources to help employees, and were back to work when neighbors often went months without income. The management team at the Arecibo plant helped employees get generators, provided food and water, and started paying employees in cash, all providing support to the people who work there.

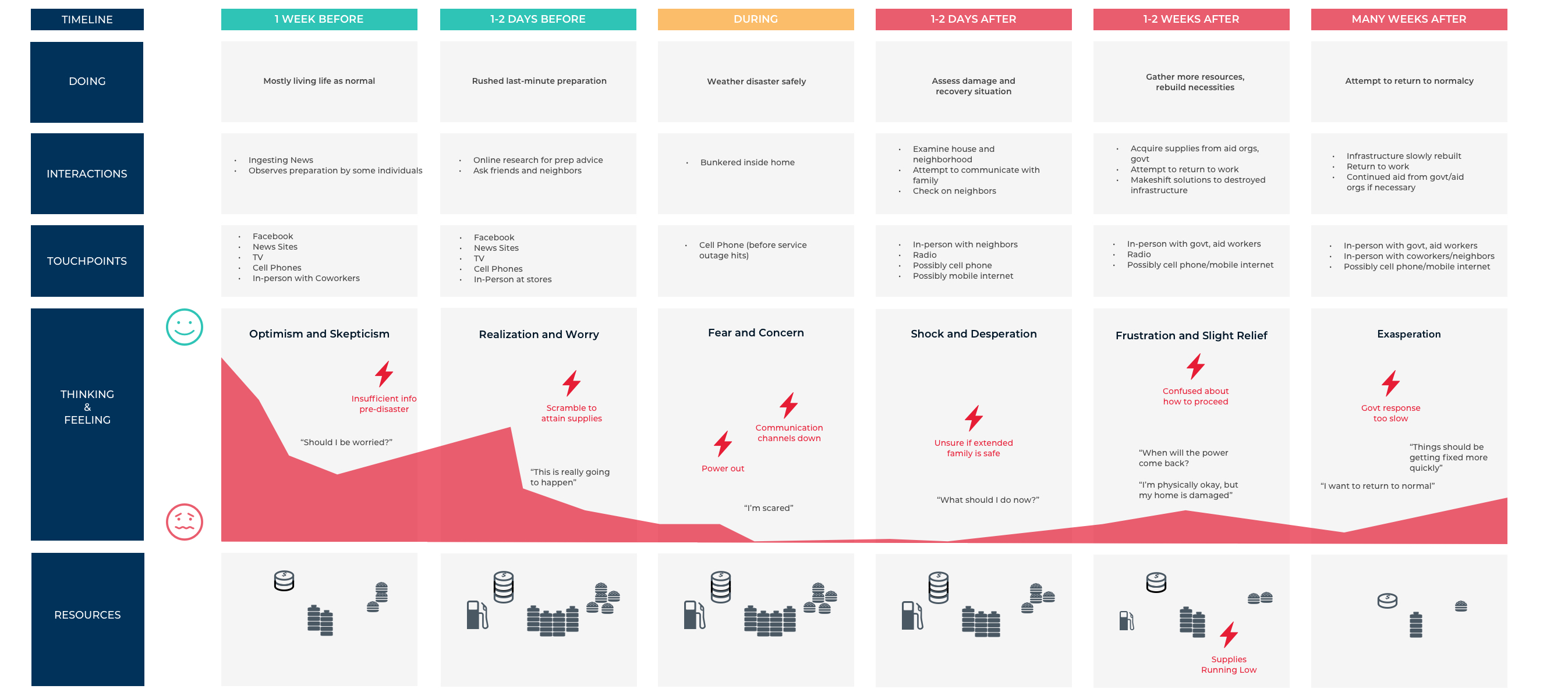

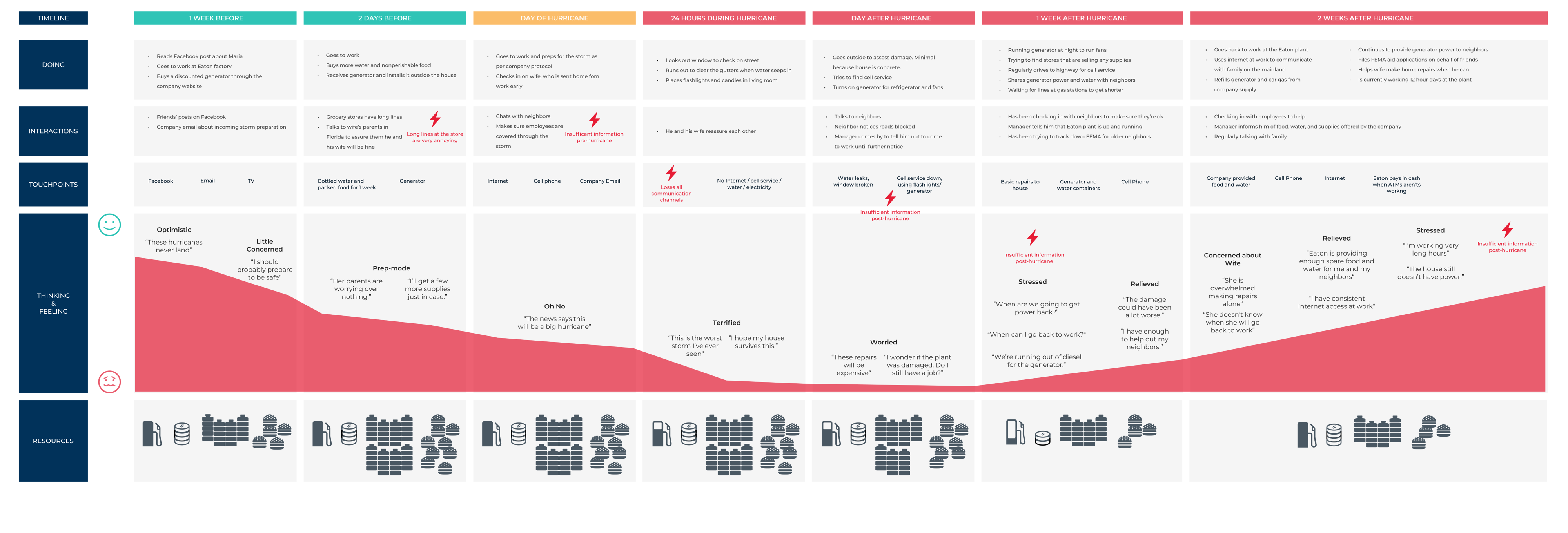

Personas and Journey Maps

From our research, we created three personas representing our users, as well as journey maps showing their experiences before, during, and after a disaster. Many of the breakdowns we saw involved communication, reflected in each person’s experience.

Carla, 42

Barolo, PR

Bio

Carla is a single mother living with her two daughters in a hilly area. She works at a grocery store and gets paid on a daily basis. She largely disregarded hurricane warnings until it was too late.. After the hurricane, her home and workplace was destroyed. She now needs to find a way to support her family without power or income.

Goals

- Get food and water supplies for her family

- Find a way to communicate with her family in another town

- Find a paying job to get money until her work place is running again

Constraints

- Dependent upon help from FEMA to support her family

- Has no way of knowing where she can get everyday supplies other than from word of mouth

Manuel, 32

Vega Baja, PR

Bio

Manuel works with Eaton as an IT manager. After the hurricane, he sees that his community is suffering and was not adequately prepared. He is able to go back to work two weeks after the hurricane, leaving his wife to clean up the damage at home. Eaton provided him with basic supplies like food and water. He decides to use Eaton’s services to help his community get back on their feet.

Goals

- Help his community

- Coorindate work schedules with his wife

- Take out time to renovate his house after the hurricane damage

Constraints

- Does not have a working phone/Internet connection at home, so he can’t communicate with his wife while at work

- Has to work 12 hours a day to get catch up on the facility’s delayed orders

Julia, 34

New York, NY

Bio

Julia is a first generation American of Dominican descent. She works at one of the most prestigious hospitals in the United States, and sees thousands of patients a year. She decided to train to be on a federal Disaster Assistance Medical Team after hearing about the horrible medical conditions in Haiti after the earthquake. She was dispatched as part of a DMAT team to Puerto Rico one week after Hurricane Maria.

Goals

- Provide medical assistance where it’s needed most

- Have her fellow doctors recognize the importance of deployed response work

Constraints

- Lack of constant communication means staff and supplies are not distributed to all hospitals

- Intermittent power outages from the generators makes it difficult to keep patients on life support

- Has to work 20 hour days to keep up with demand

- Without basic medical supplies, patients are dying of very preventable causes