Domain Research

Trends That Drove Us

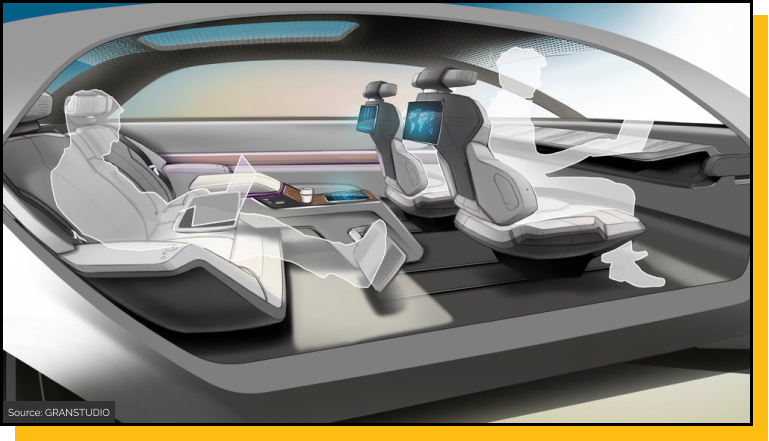

CASE is the current megatrend unfolding in the automotive industry. That is, under current trends, the car of the future will be Connected, Autonomous Shared, and Electric.

What we found interesting about the increase in connectivity and autonomy specificially is the potential impact on social interaction. Connectivity and autonomy point to a future where the car interior is a space more conducive to productivity, entertainment, and digital connection.

However, we wanted to challenge this and ask: Is this a good thing? A 2019 study on the impact of autonomous taxis showed that when the car is autonomous, people spend the entire ride on their phones. What is lost when there’s less friction around productivity and digital entertainment in the car, and how does this impact our project? We designed for the time between now and full autonomy, and we have not constrained the project to a CASE future, rather we’re using it as a guide.

In our hyper-connected world, our everyday experience is constrained by the attention economy.

Human attention will always be finite but “Today we have access to information on a massive scale.” At every moment, our attention is competed for and commoditized. Given that mobile phones allow us to, at any moment, learn anything, connect with anyone, and stay occupied, people’s discomfort with the natural pace of life has decreased, leading to what some scholars call the death of conversation.

This pervasive and constant technology use has had an impact on how young people have social interactions. A 2019 study found that the amount of time adolescents spend on digital media such as texting, gaming, and social media doubled between 2006 and 2016. Additionally Gen-Z adolescents spend significantly less time per week engaging in face-to-face social interaction with their peers than previous generations did. Further, loneliness among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders significantly increased during years when in-person social interaction was decreasing and digital media use was increasing.

It’s not only scholars noticing the impact the attention economy has had on people’s interactions. In a Nielsen Norman study involving more than 100 participants in 6 cities around the globe, they heard many parents expressing concerns about their children’s use of electronic devices. The authors distilled their findings down to two main phenomena that parents worried about, The Vortex and Filling the Silence. The Vortex is the feeling of continuously succumbing to digital temptations and being pulled away from the physical world and into the online one, and Filling the Silence describes becoming reliant on devices to constantly to fill all of the empty moments in one’s life.

In a recent survey by ZipCar, nearly half of Millennials said they sometimes choose to spend time with friends online instead of driving to see them in person.

In a recent survey by ZipCar, nearly half of Millennials said they sometimes choose to spend time with friends online instead of driving to see them in person. And nearly two out of three Millennials say losing their phone or computer would have a greater negative impact on their daily routine than losing their car. This may not be all that surprising, but it points to the trend of a decreased value placed on the car by younger generations.

In the past, cars represented freedom. Now, they are a burden. Younger generations see the burden and responsibility of owning a car outweighing the value of transportation - especially given the prevalence of other easy transportation options such as Uber or bikesharing. We’ve even seen fewer and fewer young people opting to get their driver's license over the past 15 years.

The status symbol of teens is no longer the car - it’s the smartphone. The American love affair with cars is dying, and it's being replaced an infatutation for our devices. We did, however, enter unprecedented times over a year ago when the world shut down due to COVID-19.

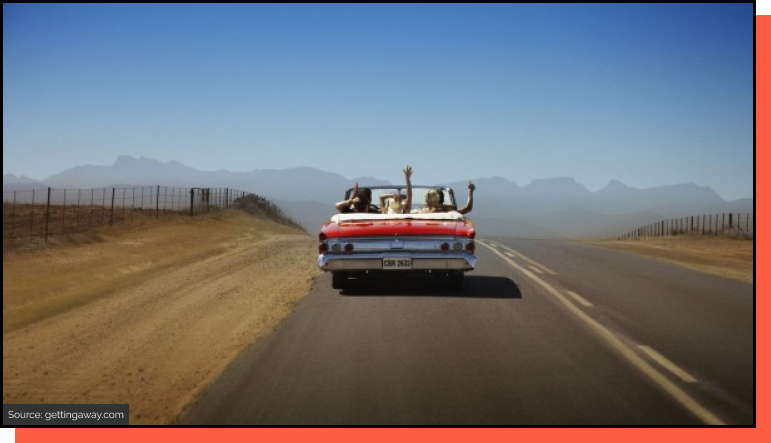

Cars become one of the only ways to safely participate in the world during the pandemic. Whether it was the reemergence of drive-in movies, the rebirth of the American road trip, or the creation of new experiences like drive-by birthday parties and drive-through graduations, COVID gave us a renewed appreciation for our cars.

A world is emerging where people could spend even more time in cars as the pandemic forces a new reality. But even if this is true, the effects of technology use that have emerged over the past few years are still pervasive. Even though we’re taking more road trips, children are engrossed in iPads and teens are glued to their phones as everyone in the family escapes to their own bubbles. The nature of the car journey is shifting, and the only question is: how long will it last?

Methods

How Did We Get Here?

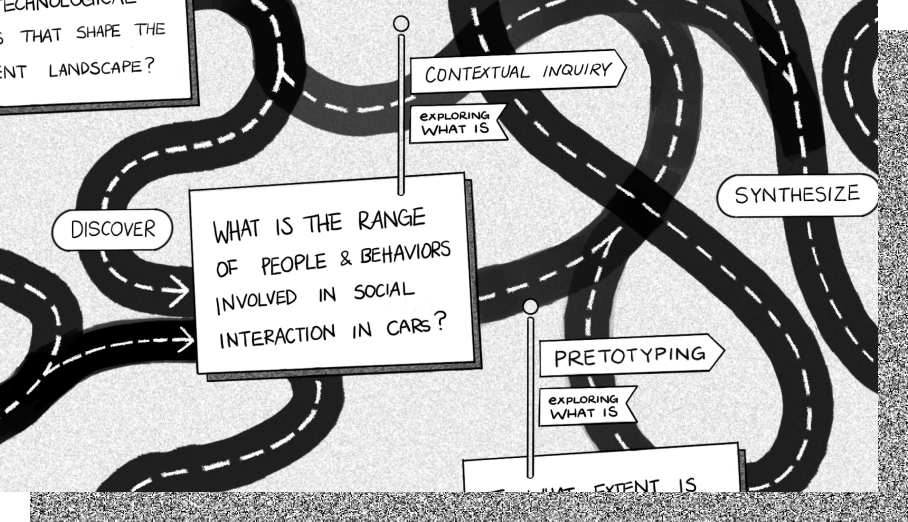

To begin defining the current state for our project, we asked: "What is the range of people and behaviors involved in social interaction in cars?"

To investigate this, we conducted 8 Directed Storytelling sessions and 6 Guerilla Interviews. We intentionally broadened` our scope and spoke with car owners, ride sharers and public transport users, asking about memorable in-person and virtual interactions in transit. We also snuck in a few intercepts at the DC airport which proved a little challenging given the pandemic!

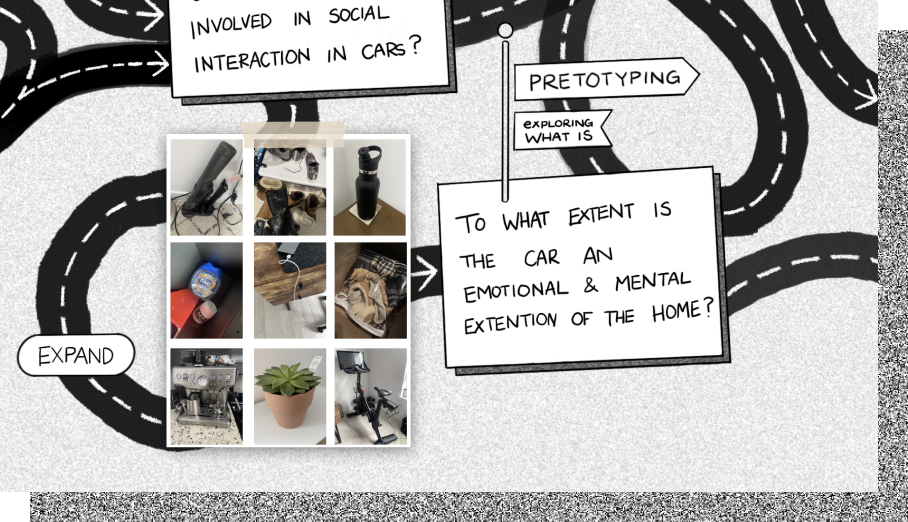

To dig deeper, we also designed a virtual scavenger hunt activity to investigate to what extent the car is an emotional and mental extension of the home. We also wondered, What are the parallels between behavior in the car and home and where do they differ? We asked our 11 participants to take pictures of meaningful items from their car and their home, items that existed in both spaces, and items from their home they wish they had in their car. We followed up the activity with a semi-structured interview using the images as artifacts, and we probed for connections between the home and the car.

To dig deeper, we also designed a virtual scavenger hunt activity to investigate to what extent the car is an emotional and mental extension of the home. We also wondered, What are the parallels between behavior in the car and home and where do they differ? We asked our 11 participants to take pictures of meaningful items from their car and their home, items that existed in both spaces, and items from their home they wish they had in their car. We followed up the activity with a semi-structured interview using the images as artifacts, and we probed for connections between the home and the car.

Because our project was about imagining the future of social interactions, we wanted to push our thinking into futures that didn’t yet exist, and we wanted have some fun with it! We used ideation as a means of gathering data, where we thought of as many social interactions as possible, and we used those ideas to stretch our imagination of what the car could do in the future. We based them around key themes we found in contextual inquiry and the car scavenger hunt activities. We then wrapped these ideas into future state storyboards to see how our 8 participants reacted to them.

After looking at findings from each individual study, we then synthesized our data holistically to derive our insights.

People don’t see time spent in cars as valuable

The constraints of the car are uniquely suited for reflection, creativity and connection.

Insights

The Road Less Traveled

As we walked through the data, we saw a consistent underlying theme that people viewed the car as a utility. It could be more, but it’s primary goal and purpose was to help people get to their end destination.

This focus on the functional element of the car reduced the perceived value of the time spent in transit. In other words, because people primarily viewed the car as a tool to get from Point A to Point B, it was difficult for them to see the car – and the time spent within it – holding any other additional value beyond its utility. The time spent commuting was just something you had to do to get to where you want to go.

We saw this in our speed dating study where we invited participants to imagine with us a world where the car could facilitate new ways to connect with each other. We introduced some neat socially supporting technologies like shape shifting seats and fully immersive visual experiences, expecting participants to be excited to explore these new potentially meaningful moments in the car.

However, we were met with uncertainty and hesitation. Participants faced difficulty imagining the car as this type of space. For them, the car’s role was not to be the destination of social interaction. Instead, they told us that the car was just a transportation tool to allow for that social context to happen elsewhere.

Compounding the undervaluation of this time in transit is the simultaneous focus on the destination. Although kids may be most explicit in this focus, with their repeated 'are we there yet?'s, this sentiment was shared universally. People want to get to their destination as fast as possible; never mind the possibilities in the time spent to get there. But this focus on the destination isn’t all bad. Oftentimes it’s driven by positive emotions, such as happiness or excitement. For example, Alicia spoke about her kids and their excitement to be where they’re headed.

The commute is viewed as an inhibitor, something that needs to be gotten through and over with for the fun to begin. This perspective overlooks the time spent in this process and its potential for connection, play, and presence. We heard from our research this dominant view of the cars of today as primarily a functional utility, with the time spent commuting a necessary component of the process with little inherent value. In fact, we even heard from some participants, like Alex who feels less guilty taking time to eat in the car. This time is valued so little that it’s like the time doesn't exist.

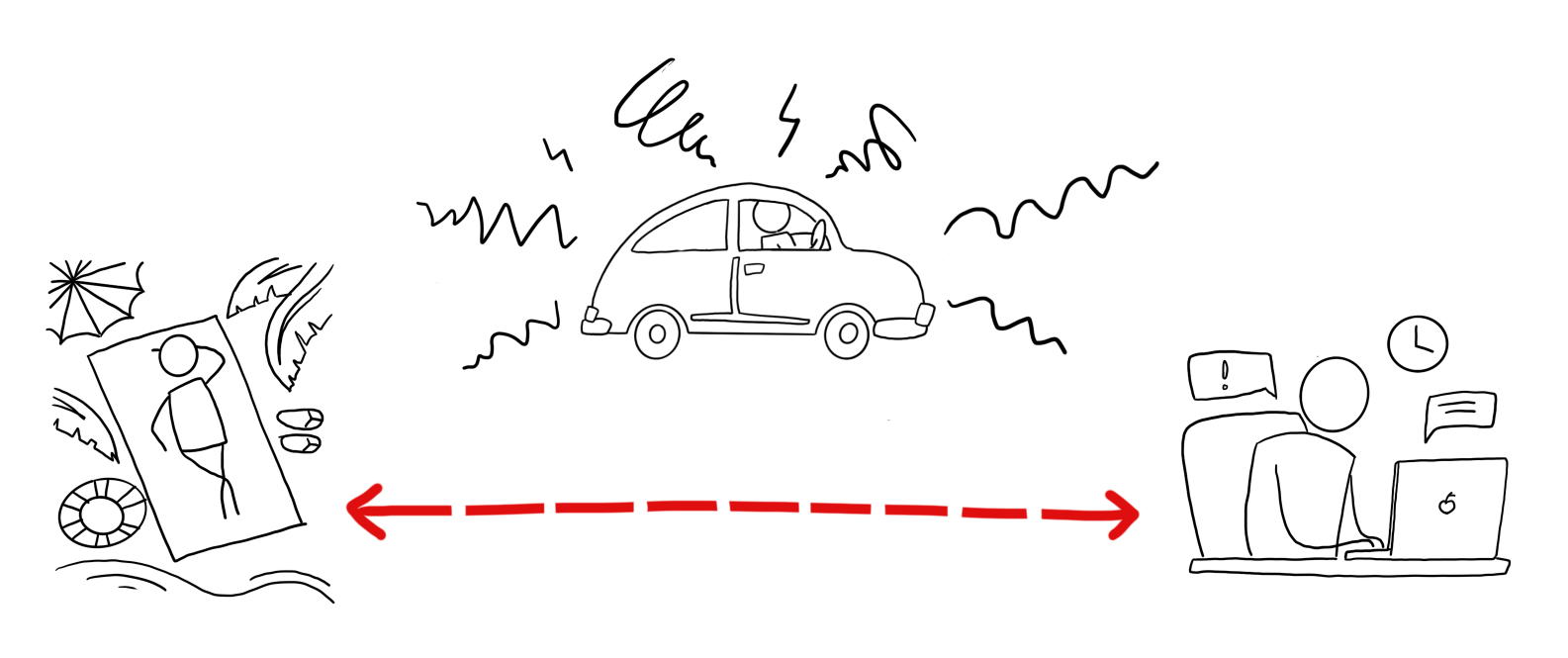

We heard over and over that time in the car was boring. But why? Why can’t you allievate boredom inside the car in the same way you alleviate it outside of the car?

When we dug deeper into this we realized that the constraints of the car force people into a state between productivity and leisure making the time feel lost. Imagine you’re sitting in your living room, and you can’t do the things you know you need to get done, yet you can't sit back and relax. This is what participants told us being in the car felt like.

We heard similar sentiments across our research as we heard participants focusing on the constraints and what they weren’t able to do. Ross had a great way of describing it.

Ross cares more about what he isn’t able to do in the car than what’s possible with the time. In other words, the constraints of the car impede Ross from focusing on what is possible with his time in it.

All of this culminates in the idea that the time in the car feels like unintentional, “lost” time, caught between leisure and productivity. Participants felt bored because they can neither relax nor be productive, and the feeling of being physically stuck compounds this to the point that the time feels as though it has slipped away. Remembering how the automobile is becoming increasingly connected and autonomous, the less people are required to pay attention to the road, the more the time in the car will open up. But knowing that people are likely to spend that time glued to a screen at the expense of meaningful social interaction, is that a world we want to live in? There’s an opportunity here to reframe the car to a space for time well spent.

While participants felt like time spent in the car was lost time, the reality is that the time exists. There has to be something happening in this time. So what do people do in this “lost” time?

We found that this perception of the car as a utility and the same constraints that make people feel like time is lost can also contribute to some pretty beautiful moments of relaxed attention, imagination, and reflection.

As we heard in our domain research, attention is a limited resource, one that is increasingly demanded and commoditized in today’s attention economy. The pressures of modern life demand constant consumption, communication, and productivity. However, the unique constraints of the car demand a level of disconnection from the outside world. The act of driving limits the ability to multitask, and it encourages respite from the world around you, making the world inside the car uniquely designed to facilitate mindful moments. Because the car isn’t fully conducive to either productivity or relaxation, it creates an unintentional third space by eliminating the possibility of doing too many things at once as Laura described.

We also saw the car used as a portable private space where people are able to be their true selves. For example, Nora told us how she escapes to her car during her workday to take a social and mental break from work, and Rebecca told us in the car scavenger hunt that her car is one of the only places she can scream and let it out, especially during COVID. It’s a space to be the “unfiltered you”. We also heard a consistent common thread of stories about moments where being in the car encouraged mindful reflection.

Hannah told us how the calm stimulation of the car allows her son to chill out and look out the window like she did as a kid rather than occupied by a screen. Thus, the constraints of the car lead to a beautiful moment of relaxed attention where drivers and passengers can simply let their minds wander.

As much as people say the car limits their freedom, they also use the car as an escape pod where they can be calm but attentive, reflective, and authentically themselves, whether that’s staring out the window or simply focusing on driving. People get to escape from the demands of modern life in a car. The constraints of the car allow freedom from the demands on their attention, leaving an open opportunity to just be themselves. This “escape pod” is a unique and rare space in life. Moments of presence and reflection are becoming increasingly rare in our modern world and the car’s constraints can be used to foster digital “disconnection” in our hyperconnected world.

Recalling our domain research, we found “death of conversation” as one major social trends brought on by social media and the attention economy. Yet when we dug deeper into primary research, we found that, in fact, the car is a place where meaningful conversations happen often.

We heard stories about people’s admissions of love, breakups, future plans, coming out, retirement, deaths in the family, exciting life announcements and other intimate stories. You name it, it’s happened in the car. What makes the car ideal for these conversations?

Early in our project, as we heard more and more about important conversations happening in cars, we started calling the car The Kitchen Table on Wheels based on the assumption that it seemed to play the same role as the kitchen table in the home; a central place where people could unpack their day and relax.

We wanted to further dissect and validate this assumption, however. Is the car really The Kitchen Table on Wheels? And if so, why? During our scavenger hunt study, Alice shared an image of her kitchen bench as a meaningful thing that existed in both her car and her home. She shared stories about her kitchen bench and how it was a natural spot for conversations. She said the car played the same role for her and her parents growing up, and she still had important conversations there.

Through our domain research, we learned there are evidence-based psychological reasons that make the car a great place for conversations. The physical constraints of the car limit distraction by not allowing people to do many other activities. It also removes a level of direct eye contact which creates a relaxed informality. Finally, being out and moving in the world while at the same being separate from it brings a level of comfort for people which promotes relaxed attention. So the unique combination of physical and mental constraints imposed by the car help foster an environment of comfort and shared purpose that allow for vulnerable conversations to happen.

Yet, as our project unfolded, we discovered that The Kitchen Table on Wheels wasn’t the full story. With further exploration in primary research, we discovered that meaningful moments involved not just deep conversations but other activities like playing games or sharing music. During our storyboarding activity, when Sid saw a story about engaging kids in creative play in the back seat, he told us about moments in the car when the whole family would make riddles together. He also spoke about the games he would play on longer rides like finding out-of-state license plates and counting cars of a certain color.

Another participant, Bill lit up when he saw the storyboard about the car encouraging a spontaneous picnic. Although the scenario we illustrated was originally for romantic couples, Bill said he would love to use this feature with his grandkids. He spoke about the joy using it to surprise them would bring. He mentioned that being spontaneous and humorous in the car is a great way for him to relate with his grandkids who were ”always on their phones.”

So the car really isn't just the ‘kitchen table on wheels’. It is also a place for play and spontaneous moments of connection. The last of our 4 insights highlights the car as a unique space to foster meaningful connections and conversations. We plan to put this unique space to work to foster moments of connection between people.

Opportunity Space

Where Do We Go From Here?

Taking a step back from our insights, there appears to be a gap, and in that gap, there is a rich design opportunity.

On one hand, valuable time is there for the taking, and there’s an opportunity to reframe the focus from what people can’t do to what they can do. On the other hand, we found the car offers a unique space to find respite from the demands of everyday life, and there’s an opportunity to put the unique constraints of the car to work for human connection.

When we overlay our domain research, our opportunity space starts taking shape. As technology and demand for autonomous vehicles increases, passengers will have even more free time in the car. Add to that the increase in connectivity in an already hyperconnected world, and this time could be swallowed by the attention economy altogether. While the pandemic has created a comeback for the car and the family road trip, bored kids in the car is nothing new, and we’re at risk of adding more screens to distract them. So if time is there for the taking, and the car is well suited to make the most of that time, we intend to design experiences that capitalize on this undervalued time and use it to create valuable moments of human connection and creativity. Where do we take it from here? Let us show you…

Pretty exciting, right? Let’s get out of the car for the moment, stretch our legs and go for a stroll. Imagine you approach a concrete wall. What do you see? Is it the lack of something more? A lack of beauty; a lack of play; a lack of connection? With this perspective, what you may not see is that this concrete wall is an open space, an opportunity. It's a space for beauty, play, and connection. All you need is chalk.

We saw that people perceive the time in the car much like this concrete wall. The time is available for the taking, but it is not being used to its full potential because people perceive the constraints of the car as too limiting to appreciate the value of the time spent in transit. We are reframing these limitations as creative constraints, and we are going to empower people to use the time they already have in transit to have meaningful interactions. That is, we are going to provide the chalk.

We intend to design experiences that capitalize on this undervalued time and use it to create valuable moments of human connection and creativity, specifically for our target users. But who are our target users?

Target User

Who Is This For?

Unique to this project is that we were given free reign to choose the target user group for whom it would be most valuable and exciting to envision the future of social interactions in and around cars. As you may have gathered, the American Family has stood out as a fascinating target group to explore this opportunity space further.

Throughout the interviews we conducted, participants kept coming back to joyful family memories made in the car. Sid recounted numerous fun games he played growing up with his family on road trips, Bill dreamt of surprising his grandchildren with spontaneous car picnics, and for Alice, the car carried the same symbolic significance as her kitchen bench. These were just a sampling of the stories we heard about the magic the car space could afford for meaningful family moments.

Perhaps what is more interesting is that the more typical frustrations of a family commute haven’t gone away; they have simply evolved as mobile and digital technologies have introduced new alternatives to keep kids engaged. But how much of a good thing is too much? Nearly 3 out of 4 parents today worry their kids are spending too much time on screens, and the car space is no different. Although kids are less restless, this tension in tech also leaves them less engaged in the present as each child escapes into their own silent digital bubble.

This tension in the car is particularly acute for families in the backdrop of a CASE and attention economy-dominated world. There is an alternative path, however, where technology can be used to break this isolation feedback loop and reclaim the car space for connection, play, and quality family time. This alternative path presents a rich opportunity for us and 99P Labs worth exploring further.