With months of research completed, we underwent a process of ideation and iteration. To ideate, we centered our focus on the primary needs of our stakeholders but for iteration, we needed to dig deeper into the field of education.

When we synthesized our research, we realized that while there are three primary stakeholders in the school system, there is a large gap that affects aspiring educators. The reality of a school's DEI Climate may very well differ from an aspiring Black educator's expectations, and this gap often leads to educators leaving the field entirely. This gap, a direct result of the variety of systemic issues mentioned in our research, leaves aspiring educators with very little flexibility to make decisions about their careers.

We uncovered an opportunity to intervene in the school system with FAME's support. The image below shows the current state of the education system when it comes to DEI Climate in schools, highlighting the lack of communication and transparency between stakeholders and an opportunity to intervene.

We began our design process knowing that we had a limited amount of time (3 months) to create an intervention to help Black educators in their careers, so we utilized scrappy methods of ideation to explore various possibilities.

Throughout the summer, our team worked to create a variety of prototypes of various levels of fidelity, each targeting a specific metric of validation. For our early testing, our team relied upon creating prototypes that focused less on visual fidelity but instead focused on the contextual use of the prototype. In comparison, the latter portion of our testing focused more on the visual fidelity of our design as well as interaction to ensure it was indeed usable.

With the goal of understanding the career trajectories of educators and finding these patterns, we began conducting what we called co-creation of artifacts with every teacher we spoke with. In these interviews, we would guide the teacher through creating a visual journey map of their career.

Through synthesizing these artifacts, we created a combined journey map that showed a path we believed every educator would see themselves in, and highlighted points at which educators would leave the profession.

We adopted a sprint structure loosely based on the GV Sprint. This involved us splitting our sprints up into 3 primary modes of work: designing, prototyping, and testing ideas quickly. The idea was for us to fail fast and iterate on our design prototypes.

Our sprint schedule spread out over 8 months.

A high-level view of our schedule throughout each sprint.

Coming out of the spring semester research, we realized the need for “analogous experiences” for early Black educators to experience before joining private schools was of the highest importance. Building off of this takeaway, we wanted to test if different levels of “embodiment” would affect how people learned what teaching a class felt like.

We parallel prototyped three different modalities to provide an analogous experience of teaching educators what it feels like to teach a new class. Each had different levels of “embodiment,” or closeness to reality:

1. [High embodiment] — In-person

2. [Mid embodiment] — Video call

3. [Low embodiment] — Text-based chat

Participants would act as “teachers,” and used a provided lesson plan to teach us a class on color theory. To create a realistic classroom experience for all the modalities, each of our team members took on personas of common student personalities and pretended to be students.

Our team used Sprint 1.0 to testing different levels of embodiment in parallel, We wanted to better understand how to provide Black educators with analogous experiences to prepare themselves for the culture shock they may experience in schools. We believed that scenarios that require a higher level of user embodiment (speaking, moving body, etc.) would increase a user's confidence and preparedness for teaching environments.

In our Sprint 1.0 prototype, we roleplayed as a class of students to cause distractions for a participant who was tasked with teaching us color theory. See pictured, there is a clear division of attention for half of the class which interrupted the lesson.

In the chat-based, least-embodied form of our Sprint 1.0 prototype, students caused disruptions using text messages and performed additional engagement by reacting to the teacher’s chats.

This sprint centered around defining the problem and our eventual intervention. We focused on defining the behavior we wanted to change, as well as the desired behavior(s) we wanted to support. This round of testing showed our team that we were too prescriptive in our initial assumption that Black educators needed analogous experiences to prepare themselves for the culture shock they may experience in schools. An important aspect of our learnings was that while we would be able to assert ourselves as experts in the field, we were not fully equipped to focus on the teaching aspect of the program, as FAME was, and is, fully equipped to prepare their fellows on how to be effective teachers.

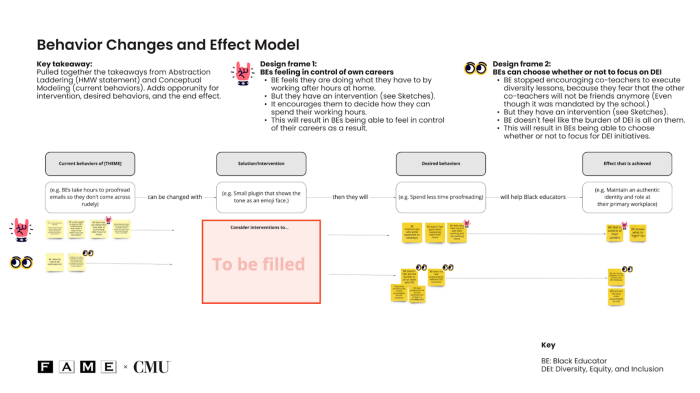

With that in mind, we scoped the behaviors we wanted to change to prevent burnout of Black educators. To do so, we created a model to highlight this change, called the "Behavior Change and effect Model."

Our Behavior Change and Effect model provided a framework for situating our ideation for Sprint 2.0.

Iterative, agile thinking at its best — we went through multiple reframing activities such as Abstraction Laddering and Conceptual Mapping to focus our design question for this sprint.

Black educators take on more work in regards to Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion (DEI), and can be changed by some intervention. They will see how they fit into the school’s policy and take on work that meets their capacity, resulting in feeling a sense of control in their careers.

We set out to define what that intervention might be in Sprint 2.0.

With our Behavior Change and Effect Model in mind, our team began to ideate new methods of intervention without boxing ourselves into a particular modality. The result of our action can be seen below, with an updated design statement of ours:

Black educators take on more work in regards to Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion (DEI), and can be changed by interacting with a model of the DEI strategy at schools. They will see how they fit into the school’s policy and take on work that meets their capacity, resulting in feeling a sense of control in their careers.

Since we wanted to show early Black educators what kind of system they will be becoming part of, the base concept was an interactive stakeholder map. It is important to note that we were not prototyping a DEI strategy altogether, but only testing how usable and understandable a new visualization of an existing DEI strategy might look. We presented the model to participants to gauge their ability to critique policies and better understand how they would fit into the school system.

We believed that if Teachers’ Academy Fellows interacted with a visual model of a school’s overarching DEI plan, then they would better understand and critique the institution, as well as their own role and capacity in contributing to a DEI plan as an educator. We recruited 5 participants, and 4 of them were experienced educators (currently or formerly employed as a teacher), while 1 was an aspiring educator (attempting to enter the field as an educator.)

A conceptual mapping our team created, informing us of what current behaviors are seen of Black Educators.

To align the team on what we were building for the second sprint prototype, Leanne whiteboard a skeleton of a protocol before we delegated work out to individual team members.

In order to build our model of a DEI plan as something for educators to interact with, Marlon and Leanne made a bunch of sketches to visualize what this model would look like.

The starting screen of our visual model on Figma highlights a few scenarios that educators can walk through, as well as the “spheres” of community members and institutional staff that are involved.

After our five testing sessions, we translated notes into stickies and grouped them through Affinity Diagramming. Along with a variety of usability issues on the interface, we found that generally, the model was able to elicit critique from most participants through directed questions that were within the interface. Our youngest participant did not critique the interface, however, which was a concern. A big success of the interface was that all teachers completed the tasks and were able to talk through what their role would be within the institution.

We translated our testing notes into stickies and grouped them through Affinity Diagramming, which resulted in a few themes starting to emerge.

We realized that our participants (those who had experience teaching in schools) were able to critique DEI policies, referencing their own experience in the school system. We wanted to move forward into our next sprint with a clear understanding of designing for two primary stakeholders: experienced educators, and aspiring educators.

Currently, experienced educators operate separately from novices. How might aspiring educators learn from experienced educators?

Moving on from Sprint 2, we decided to build off of the concept we were working with by enhancing the visual model of a school's DEI policy. Our team split Sprint 3 in half (3.1 and 3.2), focusing each half on specific stakeholders to ensure we were not only validating the need, but measuring the buy-in this kind of intervention would have:

3.1 - Working alongside 4 Black Aspiring educators

3.2 - Working alongside 3 Experienced educators and 3 Administrators

For the first half of our sprint, we focused on seeing how the Aspiring educators (in this case, FAME Fellows) responded to the critiques of experienced educators. For the second half, we wanted to provide Experienced educators with more opportunities to interact with visual models, while testing how Administrators handled the influx of information provided by Experienced, and Aspiring, educators.

As part of our two-part sprint, we relied on two modalities of prototypes. We built and tested prototypes for each, building off of our learnings along the way. For Sprint 3.1, we enhanced the school's DEI policy from Sprint 2 by designing and building a paper prototype of the policy. This paper prototype included two variations: one without critique from Experienced educators, and one with critique.

Our team first presented the first variation (without critique), before presenting the second variation (with critique.) We believed that if Aspiring educators saw how an experienced educator previously critiqued a visual model of a school's DEI policy, then the Aspiring educator would more confidently critique the DEI policy.

Our team worked to design the printed prototype and develop a testing guide during an overnight visit to one of FAME's partner schools.

The second variation of our paper prototype, focusing on interacting with provided critique from Experienced educators.

While split into 2 parts, our entire Sprint 3 elicited invaluable information, indicating that we were after all on the right track. Considering the nature of our problem, we placed less emphasis on usability issues but instead focused on the usefulness of our intervention. While we wished to test our prototypes with more participants, the results we gathered were extremely encouraging for our team.

In the first part of our two-part sprint, we saw that given comments from more experienced educators, aspiring educators were able to identify new facets of the DEI policy to be wary of and also felt validated in their own critique of the policy. Apart from usability issues, in the form of limited interactivity, information hierarchy, etc, we were excited to move forward with this approach in future sprints.

Building off of our work in Sprint 3.1, we began to tackle the ever-important question of buy-in from other stakeholders. Considering the systemic issues Black educators face, we realized the importance of testing alongside a variety of educators and administrators to gauge how they would utilize this kind of intervention. We set out to create a digitized version of the school's DEI policy from Sprint 3.1, providing participants with more opportunities to interact and leave critiques. We also created a database of information to present to Administrators as we aimed to gauge the usefulness of this platform.

We believed that if veteran educators were given a platform to voice their concerns about DEI initiatives, they would likely engage with and critique the DEI policy. Building off of that, we also believed that if administrators who oversee DEI policies were given a platform that collects and presents data about their DEI initiatives, they would bring that data into future revisions of said DEI policy.

A digitized version of a schools policy, focusing on eliciting thoughts about providing feedback while better understanding the interactions that Experienced educators would benefit from.

The data spreadsheet provided to Administrators, containing data gathered from our digitized prototype.

In Sprint 3.2, we saw that Administrators were able to identify ways in which they may be able to use the data in their jobs. While this was positive, our team was not fully satisfied that this justification would be enough incentive for Administrators to heed the feedback they received from educators. We walked away encouraged and determined to formulate a plan to secure buy-in from Administrators.

Upon the conclusion of Sprint 3, we realized the need to fully embrace all of the stakeholders in our intervention. We decided to create a value flow of the interactions that take place in our intervention to further define our design efforts. In doing so, we realized the importance of centering FAME in our intervention, ensuring that their expertise would be relied upon.

A future state value flow of our intervention, centering FAME in the middle of an entire exchange of value.

Entering our fourth and final sprint, our team underwent a serious shift. While continuing to develop our prototype by increasing the visual and interactive fidelity, we found ourselves taking a 3 pronged approach with intervention. Splitting this last sprint into phases, similar to our previous sprint, we underwent a scrappy process of iterating through multiple rounds of testing.

4.1 - Bringing our digital interface to the highest level of fidelity

4.2 - Feature prioritization leading to the development of a minimum viable product (MVP)

4.3 - Finalizing our plans for our service proposition

As we moved towards the end of our project, our team was aligned on one central point: our intervention was more than just the development of some screens. We aimed to position FAME as the experts in the Pittsburgh education space, and we set out to do just that.

As most design projects go, our team found ourselves content enough with our initial exploration and validation sessions to begin iterating our platform by not only enhancing the content fidelity, but also the visual and interactive fidelity. We created and implemented a design system to create a cohesive design for our platform, aptly titled the DEI Explorer, as we prepared for testing with all of our stakeholders.

Once we created a more solidified design for the DEI Explorer, we presented our work to FAME. We wanted to gather their own thoughts about the intervention, and how they envision the tool being implemented.

Our team worked to design the printed prototype and develop a testing guide during an overnight visit to one of FAME's partner schools.

The second variation of our paper prototype, focusing on interacting with provided critique from Experienced educators.

While our team prepared for testing our high-fidelity interface, we underwent a big pivot. After informative, and ultimately needed, conversations with FAME, our team realized that we had focused on creating an intervention that would take time and resources to implement. With this understanding, our team stepped back from our initial plans and underwent a process of prioritization so that we could still create the desired value of our intervention, but in a sustainable and implementable way.

We shifted our priority towards bridging this gap for FAME, resulting in only performing 4 tests with our high-fidelity prototype. While limited in numbers, these testing sessions validated our intervention while also uncovering opportunities to enhance our design.

With our high-fidelity prototype created, we understood FAME's concerns. Our work would only be valuable to FAME and our users if it was accompanied by a version that could be deployed immediately. This led to our team pivoting our approach to create an "MVP", or a minimum viable product.

After much of our testing from the previous sprints, we had an abundance of information about what features of our interface make or break our user's experiences. Our team underwent a process of prioritization by utilizing the MoSCoW method to not only prioritize the features our interface needed but to also determine which software would provide us with a seamless transition from our high-fidelity interface to a low-tech interface. Ultimately, our team settled on utilizing Google Sites to house our platform, as we had the opportunity to integrate multiple capabilities of Google Docs and Forms.

A digitized version of a schools policy, focusing on eliciting thoughts about providing feedback while better understanding the interactions that Experienced educators would benefit from.

The data spreadsheet provided to Administrators, containing data gathered from our digitized prototype.

With our MVP built, it was time for our team to focus on testing our intervention by putting it in front of our stakeholders. We underwent 28 testing sessions to continue validating the usefulness of the solution while also focusing on fixing usability issues that arose.

We believed that if Experienced Educators were provided with the DEI Explorer Google Doc Site (low-tech), then they would be able to critique and review a school’s DEI policy. We also focused on the other aspect of our intervention by believing that if Aspiring Black Educators were provided with the low-tech interface, they would be able to get insight into the school’s climate and engage in critique themselves. And lastly, we believed that if Administrators were presented with our intervention, they would be better equipped to gauge the success of their DEI policies while having the opportunity to enhance their policies.

Performing 28 testing sessions with a mixture of all our primary stakeholders, our team was highly encouraged by the feedback we received. With our low-tech interface, we found that Aspiring educators were able to reflect on their own thoughts by providing more nuanced critique of the presented DEI policy and corresponding feedback. We also found that experienced educators had no problem sharing their experiences and critiques about a policy. And finally, we found that the admin we tested with were excited about a system that can help them create stronger policies, especially in this era of social change as policies are being implemented without any thought of evaluation.