CHI2015: Social Microvolunteering Uses Facebook to Do Good

Photos of food. Check-ins at the gym. Political rants and memes prominently featuring cats. They fill up newsfeeds on social media, to the extent that the good social media can do is often overlooked. But a group of researchers from the University of Rochester, Microsoft Research and Carnegie Mellon University recently set out to study how the power of social media could be harnessed to help people, particularly those with disabilities.

Their paper, "Gauging Receptiveness to Social Microvolunteering" was presented this week at the Association for Computing Machinery's Computer-Human Interaction (CHI) conference in Seoul, South Korea, and received one of the conference's Honorable Mention awards.

The researchers — including Erin Brady at the University of Rochester, Meredith Ringel Morris at Microsoft and HCII Associate Professor Jeff Bigham — drew on two concepts when designing their study: friendsourcing and microvolunteering. The former refers to when social media users ask their friends to perform a small amount of work, like answering a question. The latter is used to describe when people complete a small online task for free that can benefit organizations or charities, like visiting a charity's website and answering questions that could help others.

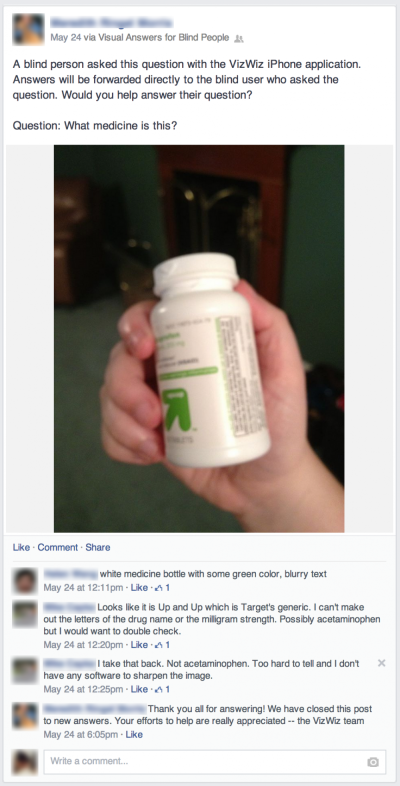

In the study, Bigham and his colleagues introduce the concept of social microvolunteering, a combination of friendsourcing and microvolunteering in which users allow access to their network or friends as a way to complete small tasks for causes they care about. The researchers recruited participants who took an online survey about their attitudes toward social microvolunteering, then had the chance to install an app, called Visual Answers, that would occasionally post questions to their Facebook newsfeed over the course of 12 days. The questions were from visually impaired people, and were generally about things in their environment for which they needed some clarification. (For example, a photo of crackers with the question "What's in the box?") In the real world, these responses would be sent directly to the user who posed the question. For the purposes of the study, though, they were not.

Bigham and his colleagues studied how many replies the questions received, how long it took to receive those replies and whether the replies were good faith answers. They concluded with a follow-up survey of participants to determine how they felt about the experience. The study's results showed that Facebook users responded positively to the Visual Answers app, and that most questions were answered quickly and correctly. Friends in the users' networks were also helpful and not annoyed, as some volunteers had originally feared.

Based on these results, Bigham and his colleagues determined that social microvolunteering is a feasible concept with great real-world potential. Future plans include exploring ways to expand into other social media outlets like Twitter or LinkedIn, investigating how to make it successful over the long term, and how to vet responses so people receiving them aren't overwhelmed or subjected to misinformation.

"While developing the idea of social microvolunteering, we sometimes referred to it as ‘donating your friends,’ which is kind of what it is," Bigham said. "Even if you don’t have money to donate and can’t be there whenever a blind person needs an answer to a question, you can give something potentially much more valuable — access to your social network and social capital to encourage your friends to help in causes you care about."

Read the paper here, and learn more about CHI here.