Online Atlas of Aquatic Insects Aids Water-Quality Monitoring

New Tool Helps Even Novices Identify Insects Inhabiting Streams, Lakes and Rivers

A new online field guide to aquatic insects in the eastern United States, macroinvertebrates.org, promises to be an important tool for monitoring water quality, and support learning how to correctly identify the freshwater insects inhabiting rivers, lakes, and streams.

Carnegie Mellon University, working with Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH), the Stroud Water Research Center, the University of Pittsburgh, Clemson University and a set of volunteer biomonitoring organizations, led development of the new visual atlas and digital field guide. It features highly detailed images of 150 common aquatic bugs, such as mayflies, dragonflies and beetles, along with a few mussels, clams and snails of interest.

Central to the research and codesign process were Trout Unlimited, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Alliance for Aquatic Resource Monitoring (ALLARM) and Maryland DNR's volunteer monitoring programs. Additional consultants included external evaluation by Rockman et al. and design support from Dezudio.

In addition to helping citizen scientists monitor water quality, the atlas is an open educational resource available for trainers, teachers and students, including those at the college level.

Marti Louw, director of the Learning Media Design Center in CMU’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute, led the three-year effort, sponsored by the National Science Foundation. She and other members of the research and development team will begin rolling out the new tool to regional environmental educators and watershed organizations at an on-campus workshop this Saturday.

“One key goal is to make the task of accurately identifying aquatic insects easier for citizen scientists, which in turn will allow more people to engage and participate in water quality monitoring and stewardship of freshwater resources,” Louw said. The number and types of insects living in waterways and bodies of water and how that diversity changes over time are vital indicators of watershed health, she noted.

Water chemistry analysis can provide specific information about water quality at any given moment, said John Wenzel, an entomologist and director of CMNH’s Powdermill Nature Reserve in the Laurel Highlands. But studying insect populations is a better way to assess the health of a stream because the presence or absence of certain insects reflects water conditions throughout the year.

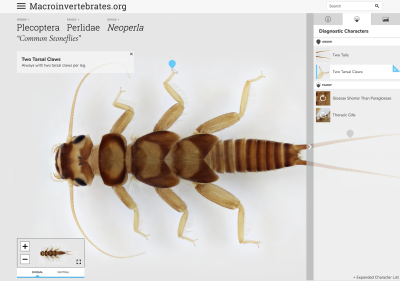

The new "Atlas of Common Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Eastern North America" includes not only explorable high-resolution images of the insects, but also detailed multimedia annotations. These help the user know what and where to look for anatomical features that will enable them to recognize orders, families and even genera. It’s not an exhaustive catalogue of aquatic insects, but includes the most common types found east of the Mississippi River.

Multiple views of each specimen collection were created at CMNH using a robotic camera rig. For each view, 2,000-3,000 individual photographs at different focal lengths and positions are digitally stitched together into a single image, enabling users to both look at the insect as a whole and seamlessly zoom in to examine tiny features.

“With this modern technology, we can turn your computer into a microscope that you can drive,” Wenzel said.

Though the field guide can be accessed online, the developers also made sure that the site would “fail gracefully” in areas where internet access is limited or nonexistent. Chris Bartley, principal research programmer in the Robotics Institute’s CREATE Lab, led the software development for the atlas and supporting image and content management tools.

“One of the lines we’ve had to walk is balancing whether this is a tool for science professionals or for volunteers and students,” Louw said, acknowledging that compromises were necessary to keep the atlas both easy to use and true to the science. “We want to honor the beauty, precision and detail in entomology to coordinate collective observation over time and place, but not let the science be off-putting for learners and first-time users.”

Wenzel has a somewhat different view.

“Going in, I thought the entomology would be the hard part,” he said. “But it turns out the critical elements are the custom software that enables you to jump back and forth between photos and facts, and the design elements that enhance learning. The individual facts and photos are nice, but by themselves they don’t teach you anything.”

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu