Author

Byron Spice

Human-AI Collaboration Can Unlock New Frontiers in Creativity

Tools Developed by SCS Researchers Show Benefits for Inventors, Designers, Songwriters

Content churned out by generative AI models is surprisingly competent, if not always particularly exciting.

But research at Carnegie Mellon University suggests that when AI serves as a partner to human designers, artists and songwriters, the results could exceed what the machine or person do separately. AI tools can help humans get out of creative ruts and explore a broader range of ideas, while humans can provide judgment — call it taste — about what people will like or if the output conveys the right message or feeling.

"It's sort of like a dance," said Niki Kittur, a professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute in CMU's School of Computer Science. "The AI leads sometimes, then the human leads, and they're sort of passing the lead back and forth."

Chris Donahue, an assistant professor in the Computer Science Department (CSD), said that partnership is crucial if artists and creators are to embrace new AI tools. He and his student, Yewon Kim, are applying AI to songwriting and have learned that if a musician doesn't think they have control over the process — if they don't feel some ownership of the product — they'll likely resist using AI tools.

Donahue, Kittur and other SCS faculty and students discussed the implications of their research into AI and creativity at the recent Association for Computing Machinery Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2025) in Yokohama, Japan.

Kittur has long been interested in how analogies inspire invention, like when the Wright brothers based a lightweight wing control scheme on a bicycle inner tube box or how engineers turned to origami to fit a solar array into a narrow rocket. The idea is that mechanisms that work in one context can be used to solve analogous problems in other contexts.

Kittur has designed computer tools to find analogies that might inspire the work of inventors, but technical limitations meant the process was a bit of a one-way street.

"In these previous systems, we were sort of throwing ideas over a fence," he said. "It was, 'Hey, here's a cool thing. Go do what you want with it.'"

But AI offers much more power for designing analogy systems, making it possible to consider far more analogies and, importantly, allowing humans to interact with the AI to explore the ideas in more detail.

For instance, Kittur and his HCII colleagues worked with Matt Hong and Yan-Ying Chen at the Toyota Research Institute to develop a tool called BioSpark that helps find analogies from the natural world to solve a particular problem or fill a need.

"BioSpark shows humans possible inspirations but also allows them to drill down to better understand the pros and cons of an idea," Kittur said.

If someone were designing a foldable bike rack, for instance, BioSpark might suggest frog legs as an analogy. The fact that they're flexible might be enticing for this application, but BioSpark would help the designer better understand how that mechanism might be used or if the frog's leg offered a particular quality they might employ in the bike rack.

Taking design cues from nature is not new in the automotive industry. It took designers 15 years to develop Structural Blue, an automotive paint color inspired by butterfly wings.

"The automotive industry has a rich history of developing biologically inspired products, a process that requires a steep learning curve to translate inspiration into feasible engineering practice," Hong said. "These tools could help designers and engineers accelerate their pace of idea exploration, both aesthetic and functional, outside the automotive domain without committing significant time and resources to do the translational work."

The BioSpark research won a Best Paper honorable mention at CHI.

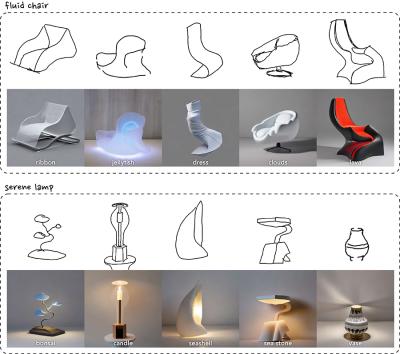

The same research team — which included HCII Ph.D. student David Chuan-En Lin and Hyeonsu B. Kang, who completed his Ph.D. in human-AI interaction — also developed Inkspire, a sketch-driven AI tool that helps designers prototype design concepts.

"If you just give people a more standard interface" — such as one that turns a sketch on a napkin into a detailed design — "you get things that look like everything else," said HCII Assistant Professor Nikolas Martelaro. "Our interface allows more give-and-take, and that helps generate more novel ideas."

"With every pen stroke you take, Inkspire will give you new alternatives," he added.

Inkspire can also accept other inputs. For instance, a user might note that they want an elegant sofa. Inkspire could help explore whether it should be elegant like a waterfall, or elegant like a bamboo garden, or simply include black elements.

Both BioSpark and Inkspire can help prevent users from falling into a rut, a common challenge that many designers and engineers encounter, Martelaro said. And because few inventions are the work of a single genius, further work will explore how a design team can use these AI tools collaboratively.

When it comes to songwriting, Donahue said AI tools are still in their infancy. Some use text prompts to generate music "end-to-end," but this output can't be edited and leaves users feeling like they don't own the product.

Kim joined Donahue's group last year to explore AI-integrated songwriting workflows, contributing to research around tools like ARIA — an AI system that extends or modifies music inputs to give artists a stronger sense of control and ownership. But it still doesn't meet all of an artist's needs.

"We found that songwriters often begin with diverse sources of inspiration beyond music, such as visuals and narratives," said Kim, a visiting student from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and an incoming Ph.D. student in CSD this fall.

As Kim and Donahue explained at CHI, where their research won a Best Paper award, they developed an extension for ARIA called AMUSE, which accepts a broader range of inputs as starting points. In addition to snippets of melody, AMUSE generates chord progressions based on photos, paintings, key words or even short stories. Songwriters can also edit the tunes and reuse parts of them.

In a user study, participants reported that using AMUSE in the songwriting process enhanced their sense of agency and creativity. Some participants said when AMUSE transformed their initial inspirations into chords, it gave them ideas for added input.

One user, for instance, used George Orwell's "1984" as their initial inspiration. "I hoped to capture its serenity and finer ambiance," said the user. "As I listened to the chords, I wanted the next four bars to progress into a darker, nonstereotypical mood. Billie Eilish's 'Birds of a Feather' came to mind because of its down-tempo, dreamy, ambient soundscape."

That user continued, "AMUSE is liberating. I feel like I'm actually guiding the tool toward what I want to create in a transformative, imaginative and visually compelling world — almost as if I'm creating music as I type."

Samples of the songs generated with AMUSE can be heard on the project website.

Donahue said if songwriters are going to accept AI assistance, it's critical that the tools allow users to employ a variety of inputs and ensure that the human can achieve the sound they want.

"We see humans as a vital part of this process," Kittur said. Left to their own devices, AI tools tend to create things that are homogenous, that are the average of earlier designs, he added.

"As humans, we always want something new and different. Many AI systems are trained almost to be the opposite," Kittur said. That's why humans must be partners in the process.

"There is no substitute for human taste."

For More Information

Aaron Aupperlee | 412-268-9068 | aaupperlee@cmu.edu

Related People

Aniket (Niki) Kittur, Nikolas Martelaro, David Chuan-en Lin

Research Areas